Image by Ralf Vetterle from Pixabay

Please find below the transcript of the interview between Dr Howard Dryden, from the GOES Foundation, and Xan Phillips, presenter of Your Green Voice.

This interview was recorded on Wednesday 26th March and first broadcast May 18th 2023 on Southampton's Voice FM. The interview is presented in three parts. (approx 7,300 words / running time 50 minutes)

Part 1: How Pollution Is Causing Climate Change

[Xan Phillips] On Southampton's Voice FM, this is your green voice, welcome to the show, my name is Xan Phillips and you are about to hear of a potential solution to climate change, that will not only instigate a new industrial revolution, but also provide a better way for people to live with nature and the planet.

However there is also a warning. That we have to act now. That time is against us because the world is focused on the wrong greenhouse gas.

Carbon dioxide is certainly a problem, but 75% of greenhouse gasses are water vapor, and as most of these come from the ocean, it was thought we couldn't influence its reduction, so we focused on CO2.

However, a new report from the GOES Foundation states that our climate problems are solvable.

But to solve climate change we need to tackle water vapor, and, as the GOES Report demonstrates, it is toxic pollution that is disrupting the oceans, and the excess water vapor that is being produced is causing the climate problems we are facing.

The Report concludes that we need a different approach to putting toxic waste into the oceans, dilution is not the solution to pollution any more.

Here to tell us more about the report's findings, and how we can quickly reduce the large amount of water vapor in the atmosphere, through detoxifying our waste, is Dr. Howard Dryden from the GOES Foundation.

Good afternoon, Dr. Dryden. How are you?

[Dr Howard Dryen] I'm very well, thank you.

[XP] You're currently sailing around the Atlantic and Caribbean, whereabouts are you at the moment?

[XP] You're currently sailing around the Atlantic and Caribbean, whereabouts are you at the moment?

[Dr. HD] Well, we're currently located in a, in a sailing vessel off the coast of Panama in the Caribbean, in an archipelago called Bocas del Toro. So we're, we're currently in a marina on the island of Bastimentos.

[XP] And what is interesting about your work is you're very hands-on, you're on the oceans, you're testing the water, you're looking at everything that's going on under the surface. So before we get into the problem with water vapor, what are you seeing at the moment in the Atlantic and around the Caribbean?

[Dr. HD] Okay, well we've been, uh, living on board our sailing vessel Copepod for the last three years. So we spent three years about one meter off the surface of the ocean. And you're right, we sailed from Scotland three years ago, uh, down to Portugal, then Madeira and Canaries and Cape Verde off the north coast of Africa, then across the Atlantic Ocean.

And we were hoping to see lots of, you know, whales and other cetaceans on our passage across the Atlantic, as well as many birds and, and fish.

But sadly, that was not the situation. And indeed, after leaving, or shortly after leaving North Africa, we got stuck. We got stuck in the Atlantic ocean, in seaweed. Seaweed called Sargassum.

Now the sargassum is, uh, a naturally occurring weed, but, we now have a massive amount of sargassum coming across the Atlantic Ocean.

There should only be about 1 million tons, but now there's an excess of 20 or maybe even 30 million tons of this stuff going across, uh, the ocean.

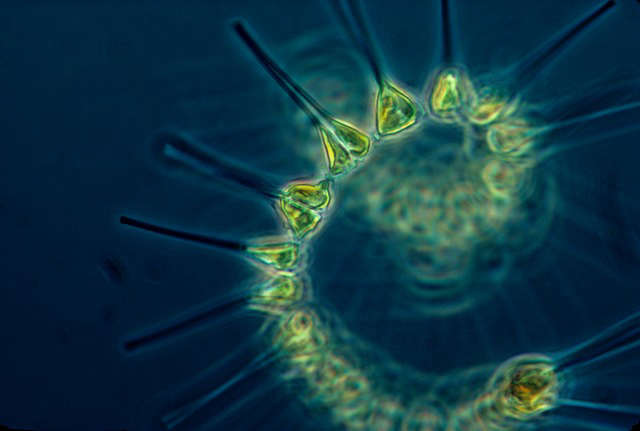

And it simply uses up all the nutrients and phosphates that would otherwise be used by the natural phytoplankton. That's the small plants living in the sea.

Sargassum in the Atlantic

So sadly, on our passage across the Atlantic, there are very few phytoplankton, and because the phytoplankton feed the animals called zooplankton, we really didn't find many zooplankton.

And because of that, there were very few fish.

So 20 days crossing Atlantic Ocean, we saw no whales. We saw no big fish. I think we saw about two or three birds as we approached the Caribbean and some flying fish, but no life for 20 days in the ocean. And we saw nothing apart from sargassum weed.

And then as we approached the, the Caribbean, our landfall was Grenada. And, we spent about three months in the Eastern Caribbean, Grenada and St. Lucia and St. Vincent's.

And again, you know, you would expect, there to be lots of, life and coral reefs, you know, in the Caribbean. And we dived on many of the, the sites and, and bays that we travelled through. And, I would estimate that 90% of all the corals gone and marine life is gone.

And it brought it home to us when we went into, a restaurant and there were no fish on the menu. Except for Atlantic salmon from British Columbia or Scotland, or, or from Chile. And that was the same with many of the restaurants in the Eastern Caribbean. No local fish because there are no local fish. They've gone.

And we're also doing a project now in the Caribbean. I've been doing water treatment for the last 30 or 40 years, retired from that profession.

But we're, we're still trying to help communities, especially rural communities and indigenous people. And apart from septic tanks, there are very few, if any, municipal wastewater treatment plants in the Eastern Caribbean.

And certainly when we're on Grenada, there are no municipal wastewater treatment plants.

Everything is being discharged into the ocean.

And when we were there last year, the government there were planning to spend 22 million dollars on an outfall.

They were bringing together all the wastewater from one of the tourist attractions, Grand Anse Bay, and simply send it one kilometer out into the, into the, Atlantic, you know, a kilometer off the beach and right onto the coral reefs.

You know, the coral are dying, you know, partially because of climate change, but primarily because of pollution. And, it brought it home to us, big style because when we left the Caribbean and headed for the ABC islands, and Columbia, then eventually into Panama, you know, the water temperatures in Panama off the coast are but one, maybe two degrees warmer than in Eastern Caribbean.

But there was 10 times more life. And the reason why that was the situation is because there's 10 times fewer people.

So where you have people, you have pollution, where you have pollution, you have destruction, especially if there's no water treatment of that pollution.

So we've decided to settle for some time in the eastern side of Panama.

In an area called Bocas Del Toro, and also in the Ginga region, which is otherwise known as Sandblast, because there is a rich biodiversity of marine life here, and we are going to try and protect that marine life and understand it.

There's also very healthy tropical rainforest, and we wish to investigate the relationship between the trees, between mangroves, seagrass, and coral reefs because mangroves, you know, are responsible for sequestering a huge amount of carbon.

They're very much more effective at sequestering carbon than terrestrial forests. And seagrass is also hugely important as are coral reefs and coral reefs are responsible for, you know, adding as a breeding ground or nursery for 25% of all the fish in the oceans.

And as the coral reefs go, then the fish go.

So that's one of the, the main reasons why we're currently based in Bocas del Toro on the Caribbean side of Panama.

[XP] Well, it's really interesting that you mentioned the mangroves and carbon because our focus as a planet. Really has been on reducing the amount of carbon in the atmosphere. It's the number one thing that most environmentalists would say that we have to do.

But in your report for the Ghost Foundation, you say there is too much water vapor in the atmosphere and water vapor should be treated as the most serious greenhouse gas. Can you explain to the listener why we have too much water vapor in the atmosphere?

[Dr. HD] Okay, well carbon is, certainly very important with regards to climate change because CO2 is a greenhouse gas but equally methane is, is also very important, but collectively with carbon dioxide and methane, they account for about 25% of all the greenhouse gasses, by far the most important greenhouse gas is water vapor. It's humidity.

And the accepted position is, well, we can change CO2 levels. We can affect methane levels, but we cannot change the concentration of water vapor in the atmosphere.

So this is an area that we've been looking at and there's two main ways; or two sources of water vapor.

You have transpiration of water from trees.

That's why you have rainforests. Because transpiration of water from the trees, you know, is responsible for about 20% of the water vapor pressure in the atmosphere.

80% of the water vapor in the atmosphere comes from evaporation of water from the oceans. And also aerosols from the oceans.

And it is quite a complex inter-reaction between water vapor and aerosols.

Rainforest Image by Bishnu Sarangi from Pixabay

Aerosols, you know, are like small particles of water, so you know, primarily the oceans are responsible for the humidity and water vapor pressure in the atmosphere.

And the rate at which water can escape into the atmosphere depends on that surface boundary between the water and the air.

Now the oceans cover 71% of the entire planet and on that surface layer, and it's only one micron, one between one and a thousand microns thickness, there is a lipid layer.

It's an oil film, an oil surfactant film, and I think everyone will have heard of Omega3 oil and think that it comes from eating oily fish.

Well, that's true, but the actual source of the omega3 oil are plants living in the ocean and that Omega3 oil simply gets transferred up the food chain to oily fish.

So the source of the oil are marine plants or phytoplankton.

Phytoplankton

And when phytoplankton grow, they produce Omega3 oil primarily, a species or groups called diatoms, which are made from silica and carbonate based colifor phytoplankton.

And they use the oil as an energy store and as a means of buoyancy. And if they want to go down, then they can release oil. And that oil then ends up on the surface of the ocean.

And that oil forms a skin. And that skin can slow down the rate of evaporation and gas transfer of not only water, but oxygen and CO2 by as much as 50%.

So phytoplankton are regulating surface water evaporation by as much as 50%. So that's a huge amount.

Now they won't stop water vapor going into the atmosphere, but what it will do is reduce the rate at which it enters the atmosphere.

Now the next factor, that the oceans are responsible for, and phytoplankton are responsible for, are the aerosols. Now aerosols are hugely important because you need an aerosol to nucleate water vapor to form clouds.

Without aerosols, and without particles in the atmosphere, you don't condense the water to form clouds. Now the aerosols, again, come off the surface of the water.

Whenever you have a breaking wave, then, very small, you know, some air gets in-trained and when that air then breaks the surface, it creates aerosol of water, water vapor or water particle, and it's the biogenic nature of that aerosol, it's the phytoplankton content and all the other bits of, marine life that are in the aerosol that catalyze the nucleation and condensation of the water.

Image by Roger Mosley from Pixabay

So we need the aerosols and we need that biogenic aerosols.

And without the aerosols containing the bits of plankton and chemicals such as dms, dimethyl sulfide, then you won't get nucleation of water and the formation of clouds.

So what then happens is the water vapor pressure increases in the atmosphere, and as it increases, the temperature increases. And if you don't have the aerosols to form clouds, your clouds are almost like the, the safety valve for the energy in the atmosphere.

When you get cloud formation, you're doing several things.

First of all, the clouds are helping to reflect energy back into space.

And also when clouds form, or when water goes from a gas phase into a cloud to form the, the small water droplets, that latent heat of energy is released, and that's what powers the wind.

So, if you have a situation where you have high water vapor pressure and then you have a trigger event to form a cloud, under those conditions, because there's a huge amount, or more energy in the atmosphere, when clouds do form and, and they will form as a consequence of, of pollution.

As one example, you know, the torrential floods in, in Pakistan last year (2022), we believe that it wasn't caused by climate change it was caused by the lack of water aerosols in the atmosphere, and then pollution from China triggered the formation of clouds.

And because you had that trigger event taking place when you had a high water vapor pressure, then you got massive cloud formation, you got massive release of energy, incredibly strong winds, and then torrential downpours.

That's what climate change is about. It's not just about CO2 formation, it's a rate of change of water vapor pressure in the atmosphere.

And the same thing is happening in the oceans. And as we lose the marine biodiversity in the marine phytoplankton, we lose that surface skin of the oceans, which means that water vapor pressure increases very rapidly in the atmosphere, because of the lack of aerosols, we don't have that safety valve to remove that energy from the atmosphere.

So you'll get torrential downpours when they happen.

But you'll also get very high wind velocities, which might only last for maybe five to 20 minutes.

And we're now seeing that. We're seeing it for example, in Italy in the, the south of France, you last year in Corsica, there were winds that blew up to 200 kilometers an hour, just lasted five or 10 minutes.

So what we're gonna see is very high wind velocities, torrential downpours, in areas where the SML layer has been impacted, because we have higher water vapor pressures developing in the atmosphere, and the Mediterranean is an example of that because the Mediterranean has largely lost its surface micro layer (SML).

So countries surrounding the Mediterranean are going to experience more and more extreme weather conditions, which will swing between drought, torrential downpours, high temperatures and very high wind velocities.

So keep an eye on Italy, Greece, and the south of France, that's where it's going to happen, and that's where it is happening now.

[XP] Your information is really interesting. It's absolutely fascinating and makes me wonder, are you, because, because everyone's so fixed on co2, are you like a lone voice that's going against science or current scientific wisdom?

Are you finding it hard to get anyone to listen to what you are saying about the surface micro layer, about the aerosols, about the humidity in the atmosphere? Or are people slowly waking up to this fact?

Dr Howard Dryden speaking at COP26, Edinburgh.

[Dr. HD] Well, you know, everything that we're talking about, you know, has been the subject of research for, for many years. But I would say 99% of the focus with regards to climate change is with CO2.

But CO2 or carbon dioxide is a minor greenhouse gas. By far the overriding factor controlling and regulating the climate are clouds, water vapor, and interaction, you know, between the atmosphere and the ocean.

We have totally ignored the oceans, 71% of the planet, and we haven't really considered their impact and role in regulating our climate.

And indeed the UN I think it was, acknowledged the oceans could be important in 2015. We're only now also considering the role of biodiversity in climate change.

So there are, you know, groups aware of these issues. But I would say that there is virtually nothing, you know, being done in this, this sector.

And again, the opening statement at the UN Conference on the Oceans last year (2022) in Lisbon was that 80% of all municipal wastewater in the whole world is discharged without any treatment into the oceans.

And this aspect was considered to be extremely important, you know, at the Ocean Conference, but that was the extent of it at that conference.

There were no water companies present and there was no discussions as far as I understand, on effluent and water treatment.

So how can we solve these problems when we continue to discharge, you know, toxic waste, into the rivers and into the oceans.

And you're right, you know, the, the mantra of the water industry, has and still is, the solution to pollution is dilution, and that's fine for chemicals that dissolve into the water, but the most toxic of chemicals do not dissolve into the water.

They're referred to as hydrophobic and lipophilic.

They're oil-like chemicals, and they simply float on the surface of the ocean and they then interfere with the SML layer, they're destroying it.

And also, because they don't dissolve in the water, they concentrate on other particles, like plastic particles that are also hydrophobic, and these hydrophobic plastic particles, and also the partially combusted carbon from the burning of fossil fuels (shipping), they're all sitting near the surface.

They're absorbing these lipophilic chemicals, toxic forever chemicals like PCBs and DDT and PFOS.

And they concentrate the chemicals many thousands, if not millions of times. And each particle then becomes food for the zooplankton.

And that's why the zooplankton animals are dying on the planet.

That's why the fish have very high levels of PCBs. That's why most of the whales have concentrations of PCBs and dioxins 50 times higher than would cause brain damage in humans.

And we're doing this to the entire ocean.

So it's not surprising that ecosystems are beginning to suffer and to collapse and to break down and it's not surprising that the surface micro layer is disappearing.

And it's not surprising that water vapor pressures are increasing, and cloud formation have been decreasing since the 1980s. It's tracking the biodiversity in the oceans.

From the 1950s, cloud formation was increasing and temperature was decreasing up until the late seventies, early eighties. Then we hit that reverse point, the counterpoint.

Then everything started to fall apart, and it's progressing at an accelerating rate.

So that we believe is the primary mechanism, you know, for climate change. And it's also one that we have the capacity to reverse.

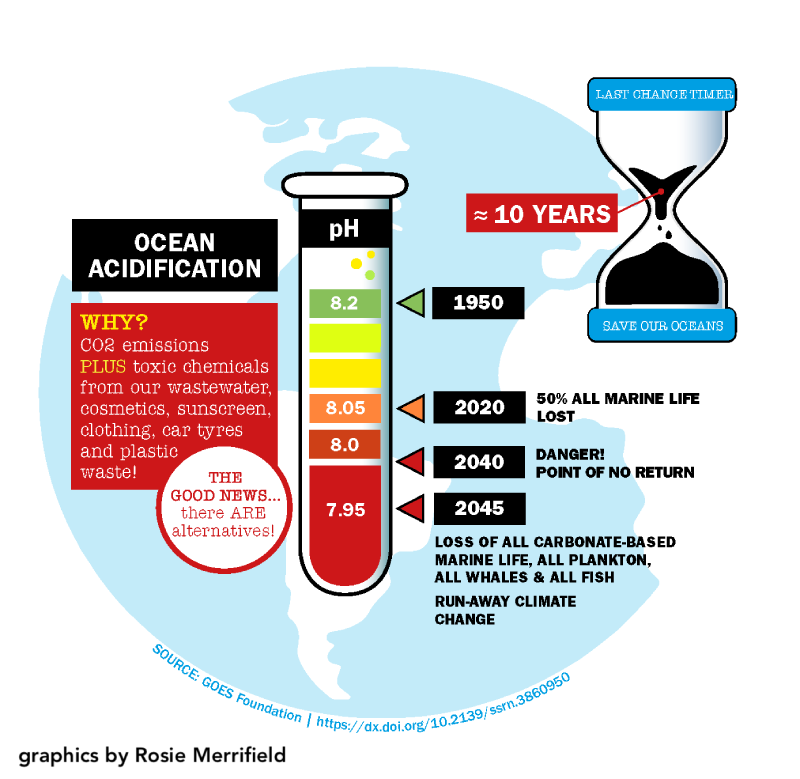

We'll never stop climate change by reducing co2. Because if we're carbon neutral tomorrow, or at least by the end of this decade, then atmospheric concentrations of CO2 will still pass 500 ppm, and oceanic pH will still drop below 7.95.

And the reason why that is important is because 50% of all marine life living in the ocean, or at least plankton living in the ocean, are based on forms of carbonate that will have dissolved by the time the pH drops to 7.95.

And when that happens, the SML layer completely collapses and we have uncontrollable climate change, irrespective of the concentration or the production of CO2 for the burning of fossil fuels.

So CO2 is important. but it's only part of the picture, and unless we address the loss of nature, the loss of marine life and terrestrial life, then there is no possibility of stopping catastrophic climate change.

You know, even the recent report from the World Wildlife, you know, stated that we have lost 69% of wildlife from the world, up to 90% in Central and South America.

They weren't referring to the plants, but 70% of wildlife is incredible, and the rate at which we're losing wildlife, within the next 20 years would've lost an excess of 90% of all wildlife on the planet.

Even now, if you include humans and farm animals, they represent 94% of all mammals, terrestrial mammals on the planet.

So we only have 6% of wild mammals left on the planet and they are responsible for looking after our ecosystem, and they'll be gone, gone within the next 20 years.

Then you look at the, the insect population, so it's right across the board.

Part 2 - Detoxifying Can Stop Climate Change

[XP] So how can we fix this, Dr. Howard Dryden? How can we save, prevent, or reinforce the surface micro layer and start bringing balance back to the planet?

[Dr HD] Yep. That, that's the key word balance. And that's what, you know, the American Indians and indigenous people all around the world are acutely aware about is balance and harmony with nature.

We have to restore that balance.

You know, the indigenous people of the world represent 5% of the world's population, but they look after 80% of the environment.

So, you know, we have to look after the indigenous peoples, again, one of the reasons why we're in Panama. Working with the, the Guna Yala and the Embera and the Ngäbe, who are looking after the environment.

So we're giving them as much of the support as we, as we possibly can.

But we have to, we restore nature. We have to regenerate nature, both terrestrial plants and animals and all. So marine life living in the oceans because we all depend upon nature for our various survival.

You know, herbicides and pesticides have destroyed nearly 80% of all insects, within the next 20 years will have wiped out most insects on the planet.

So how do you expect, uh, the pollination of plants and agriculture to survive?

So we are intrinsically connected and linked to nature. So we have to regenerate and bring back nature.

And one of the, the main things that we can do is, stop destroying it.

Stop destroying it by pumping toxic chemicals into the environment, we have to clean up our atmosphere, clean up the soil, clean up fresh water and clean up the oceans, and we can start doing that by treating our waste, by removing toxic chemicals and any atmospheric discharges.

And by removing any toxic chemicals and plastic in our water and, and wastewater, you know, we have to stop killing life.

And we all then have and, and it won't be good enough just to stop doing that, we also have to start doing some good.

We have to start regenerating to restoring ecosystems, to restoring mangroves and seagrass and wetlands because these are the environments that give balance.

They give biodiversity, and the more diverse an ecosystem, then the more stable that system becomes.

So that's what we have to do is to bring back nature, to bring back life.

[XP] If you were in charge, Dr. Dryden. If Dr. Dryden was given the funds and the manpower to do this, how long would it take do you think, to put the brakes on climate change and start getting, start getting close to balance at least?

[Dr HD] Well, we're all dependent upon nature, and for terrestrial ecology to double in biomass would take 60 years.

But for marine life to double in biomass would only take three days, because the vast majority of marine life is under one millimeter in size and has a doubling time of three days because 60% of marine life, you know, are your plankton, are your plants and small animals and bacteria, and they are the main driver.

They are the life support system of the planet. So recovery could be super fast.

But we have to stop killing them. We have to stop the toxic chemicals going into our environment.

So that's the first thing that we would do would be to, there wouldn't be a first thing, you'd have to do everything in parallel, but it makes no sense to discharge toxic chemicals into the environment without any treatment. We have to remove them.

We also have to think well. You know, do we need, you know, do we need a toxic chemical or is there another way of manufacturing a product that avoids the use of toxic chemicals.

We have to engineer toxicity out of our life?

You know, that's the definition, or one of the definitions of a circular economy is to engineer out of that circular economy any toxicity, because if you have toxicity, it's not circular and it's not sustainable.

So if we are going to survive on this planet, we have to eliminate toxic chemicals and have a truly circular economy.

So, if we can't remove the chemicals, the toxic substances from our environment, by changing the way in which we manufacture, then we have to immediately start to treat our water and wastewater to stop getting into the environment.

Then we can work on eliminating the chemicals and substances in our manufacturing processes.

So, there is actually a potential here for a huge boost to industry for green products and green chemistry. We don't have to stop, you know, doing things. We just have to change the way in which we do it.

[XP] With 80% of the world's waste water from land, from sewage, from industry, going, going straight into the ocean. To stop that within a couple of years would take a massive effort.

[Dr. HD] Yeah, you're absolutely right. It would take a massive effort. That would be if we're doing things in a conventional way, you know, I'm sure very few have actually gone round, people in Europe or North America, have gone round an effluent treatment plant, but the vast majority of them are built by engineers.

And they're based on the design that's over 120 years old. And, they are mainly [built] to address, you know, organic matter and nitrogen.

But, one of the things that I've been doing for the last 30 or 40 years is using biology to treat water and wastewater.

And you can actually treat wastewater much more effectively, and at a much lower cost, up to 50 times lower cost by using nature and supporting nature to treat the water.

For example, extended diffused aeration lagoons, and wetlands, are a perfect way of treating water.

The English village near with a pond in the middle of the village. That was historically the way of treating the wastewater.

It would all flow into the center of the village where you'd have a duck pond, and that was your wetland. That was the effluent treatment plant.

And as long as it wasn't overloaded, it would effectively treat that wastewater coming from the village.

But now we have toxic chemicals in the water, so we need a different approach to it. We need to support nature. At a higher level to treat that water in wastewater.

And certainly by doing it, using as one approach, extended diffused aeration, 15 day residence time as opposed to six hour residence time, then we can treat that wastewater.

Now the other planetary boundary that we have crossed is the shortage of fresh water. Because we're discharging, we're wasting all our water, by not treating it.

And, you know, we can quite easily treat our wastewater and turn it into usable freshwater again.

So effluent treatment not only prevents the damage to the ecosystem, but it also gives us water, which can be used for human consumption, for animals and for irrigation.

So we start to close the loop, we start to recycle. So it doesn't need to be a cost. These systems could actually make money. For social enterprises.

So that's why I think it could be done very rapidly because you turn it into a business.

[XP] Have you got a timeframe?

[Dr HD] The timeframe is being dictated by nature and by the rate of ocean acidification.

I consider that unless we are non-toxic, potentially by the end of this decade. If we don't achieve that target then because of the huge inertia there is within the ocean ecosystem, we may be too late, unless we address these issues now and have a non-toxic world by the end of the decade.

So it's almost an impossible task to achieve that, but with growing awareness of the issues.

And, there was a recent report. Just came out, about seawater temperatures in the Atlantic off the east coast of America, were 14 degrees C warmer in March this year than there have been in the last 20 years.

14 degrees C rise in March, in the Atlantic Ocean, means that the marine life will not survive those conditions. And it will accelerate the melting of the Greenland, icecap and glaciers.

It means there will be more fresh water on the surface of the Arctic. It means that we'll have destroyed the SML layer, and that's one of the reasons why the Arctic is increasing in temperature four times faster than anywhere else in the planet.

Everything is connected. It's a chain reaction. And we're in danger of closing down the Gulf Stream.

It's already dropped, or reduced and speed by up to 20%, so we could be entering the "Day After Tomorrow" scenario, where it's not an increase in temperature that'll happen in the Northern Hemisphere, it's a rapid decrease in temperature as the Gulf Stream slows down and that's happening, so we don't have long to turn these series of events round, we can still do it, but we have to act now and act on a, a huge scale, around the world to affect any change.

PART 3 - Action Required By Humanity

[XP] So what do you need people to do? What would you love? Let's start with your fellow scientists and then, and then drift down to the public and maybe end with the politicians.

[Dr HD] Okay. Well, the fellow scientists have to acknowledge that there is a problem there in the first place. And, and many of them, I'm sad to say, have vested interests in carbon. That's where they're getting their money from, their grants from.

There are quite a number of dissenting voices now, especially from the IPCC, because of the inactivity by governments and the UN to actually do something.

But we have to now, and indeed the report from the Arctic, that it was claiming that the Arctic ice is melting six times faster now than it was a few years ago.

They're actually saying that there is now nothing we can do to stop the melting of the polar ice caps we're too late, but that's based on CO2 as a means of regulating climate change.

We have to acknowledge that there are other factors responsible for regulating the climate. And this blind focus, or carbon tunnel vision, on CO2 is actually now our biggest problem.

We have to wake up the scientific community, that there are other mechanisms involved, and many are acutely aware of that.

But then where does the money come from to affect that change? Because it's all based on carbon credits. Uh, and now we're seeing carbon greenwash where companies and organisations are setting up, you know, to plant more trees or to recycle plastic or to store it in warehousing, which are effectively doing nothing, but that's where the money is going.

So we have to change that mindset. And, I'm not sure how that could be done, but that's what has to be done. And also to raise the awareness among people, and individuals of what they're doing on a, on a daily, on a daily life.

You know, for example, I used to have an electric car, until I realised that electric cars were maybe 50% heavier, than a petrol combustion engine.

And at the tires, tire wear on the road was discharging toxic microplastics. And because of the higher torque of these engines, they were actually more polluting than a petrol combustion engine. So again, it's aspects like that we have to raise awareness about.

The fact that many cosmetics are horribly toxic.

One chemical called oxybenzone, it's used in sunscreens and two and a half thousand cosmetics is toxic to marine plankton at a level of 62 parts per trillion.

If you were to discharge 70,000 tons of this chemical into the oceans all at one time, it kills everything. But we're discharging 20,000 tons of this chemical every year just in sunscreen.

So, why is it still there?

So, you know, my recommendation to your listeners is look at the label on the bottles. If it contains oxybenzone or parabens or silence, don't buy it.

Not only is it toxic to the environment, is toxic to to you as well, horribly dangerous and, you know when you use these chemicals, they're discharged, you know, down the drain or down the toilet, you know, they go through the sew works into the rivers and then back into the sea, and it's oxybenzone, which has been considered to be the primary reasoning for the destruction of coral reefs.

So why don't we stop it?

There are lower cost alternatives, just using zinc oxide, or titanium dioxide, mineral sunblocks.

It's an example of something that we can change tomorrow. It's not gonna cause anybody any problem, but it'll have a huge impact on the environment.

But oxybenzone is still being manufactured.

It's used in cosmetics, it's used in adhesives, it's used in paint. It's used in a thousand different other products, but it's wiping out marine life, marine life upon which we all depend, but we could change it tomorrow and nobody would notice.

There's lots of things we can do that'll have zero impact on, on people's, you know, day-to-day life, but will have a huge impact and benefit for nature.

[XP] Does this go back to doing no harm?

[Dr. HD] Do no harm. It's a Hippocratic oath for the environment.

You know, we've also been working with the NHS (National Health Service) and doctors and they have a Hippocratic Oath to do no harm to people.

But you know, the drugs and the antibiotics and the pharmaceuticals that are consumed, they end up going into the rivers, into the environment, and many of these chemicals, by their very nature, aren't very stable and they're very bioactive.

And they're, they're having a huge impact on, on river systems and environment.

So, you know, the NHS in the UK are now looking at, well, what can we do to stop this? How can we make it better? You know, are there alternatives to the pharmaceuticals that we are using that are more environmentally friendly, while still being effective as a medicine?

You know, informing their patients "do not discharge these products down the toilet". You know, bring them back to the pharmacy where they can dispose of them properly.

And in Germany, you know, they're actually using small carbon filters that you pee into to try and capture these pharmaceuticals before they go into the toilet.

So again, there's lots of things that we can do to protect nature, to protect the marine ecosystems, but it's also protecting our own water supplies.

Because if you take, you know, many rivers in the UK, especially the Severn and the Thames, you know that water is used maybe six or more times before it reaches the sea.

Every time you take a drink of water, you're consuming at least five or six pharmaceuticals and the same number of toxic chemicals. So it's poisoning us, you know, life expectancy has been increasing up until relatively recently.

Now it's decreasing. Because of the toxic load that we're all exposed to from the water that we, we drink and from the food that we consume, but also in contact with plastic and other chemicals in our home.

You know, when you buy furniture, it will probably have stain shield on it.

It's PFOS, you know, it's the plastic, which is now recognized to be one of the most toxic chemicals on the planet, but your furniture might be covered with it. Your carpet might be covered with it.

Then you have fire retardants, PBDE, which are incredibly toxic to the marine ecosystem and to people.

So, we have to rethink what we are doing. We have to rethink what goes into products that we are in contact with, that food is in contact with, you know, plastic food containers.

You know, how insane is that? You know, the level of toxic chemicals that are being transferred from that plastic, you know, into the food.

Cardboard containers are quite often quoted with PFOS on the inside to stop the cardboard from degrading. So you think you're doing good buying a cardboard, food container, and you end up actually with higher levels of PFAS contamination.

[XP} This is, I mean, this is so crazy, Dr. Dryden, because the changes that you are suggesting require legislation. It requires people to think about it.

It requires a movement, a body of people to say, this is where we gotta go. And it just feels that the movement is not there in front of us. It could take 10 years before people go, yeah, maybe that's a good idea.

There's got to be something that can wake people up, something that's really obvious. Do you think there's gonna be a something that happens that people are gonna go, yeah we need to act?

[Dr. HD] Well, before I answer that one, I'll give you another example. There's an insecticide called neo nicotinamide. Which the farmer lobby in the UK, have managed to, you know, turn the government.

The government actually banned it a year ago, but the farmer's lobby in the UK managed to turn that ban over, to allow it to be used.

Neonicotinamide is an insecticide that's actually addictive to insects. The insects now seek out, especially bees.

And it's been instrumental in probably wiping out most of the flying insects, or a high percentage of the flying insects in the UK and Europe.

Yet we continue to use it, and if we continue to use this horribly toxic chemical to insects, then there will be no insects in 10, maybe 20 years.

Then agriculture collapses.

You know, I fail to understand the, the sanity in, in these decisions and that that's one that's very obvious. So I do fear for the future if we can't turn over the use of horribly toxic insecticide like neonicotinamide.

And, so, you know, I'm really concerned. About what's going to happen.

[XP] Yes. I think, uh, there's not much more we can say apart from wake up everyone and, and read the GOES report.

[DR HD] Yep. Well that would be a, that would be a good start and especially governments in industry that, you know, we have to wake up, that we are all part of nature. We are dependent upon nature.

And even if humanity went extinct at the end of this decade, then nature will also largely go extinct because of our toxic legacy.

Nature will not find a way with this one, because of all the herbicides of pesticides or PCBs, mercury, dioxins, the PFOS that we currently have in the environment.

So we have to stop destroying the environment, but that's not enough. Just like reducing CO2 emissions is not enough. We have to start doing some good, we have to start regenerating.

And there is a push now, especially in, in the USA for regenerative agriculture, you know, to stop the use of herbicides and pesticides and to use more natural ways of farming, which, perhaps are not quite as productive, you know, as the, the way in which we're doing it now.

But what they're finding is that they're actually more, economic, and they can potentially make more money by employing regenerative agriculture.

And that's what we have to do with everything. You know, any industry, manufacturing a product or a chemical have to look: "Well, am I doing harm? Is there a better way of, of doing this?"

And everyone should have a policy of 'to do no harm to the environment and to people' and to 'support and regenerate nature'. And that's one of the things that we're trying to do now here in Panama, in Bocas Del Toro.

We've taken on a, a small piece of, of land that we want to turn into an environmental center to demonstrate sustainable living, to do no harm, to actually start to do good to the environment and to use that demonstration to help the indigenous people living in the area, but also to help and support tourists, to show that there is a different way of doing something.

And also with the Panamanian government, you know, and as a marine biologist, you know, living in Panama now we have the Atlantic Ocean on one side and the Pacific Ocean on the other side, and about 25% of the world shipping industry going through the canal. Or a high percentage, maybe it's not quite 25%.

But, on the news yesterday, on the BBC World Service, they were reporting that, ships are having to, well, basically, Panama, that gets five times more water than Scotland is running out of water because of climate change, because of a change in the environment, which means that the Panama Canal can no longer be operated, which means that ships can't go through it, which means they have to take a 8,000 kilometer detour around South America, which will simply burn more fossil fuels.

So, you know, everything's connected, and interestingly, just a, a side part to that, we're working with the, the Embera indigenous people in the Shangri National Park in Central Panama.

Absolutely stunning tropical rainforest and, people, and we're helping them with their drinking water supply, which comes from a spring, quite high up in, in the mountains, near their village.

And, this spring comes out between the roots of one enormous tree.

And this was the inspiration of James Cameron's Avatar. It was based on this village and the tree of life, and when we took water samples from the Tree of Life in Central Panama, we found up to 10 particles of plastic in every liter of water.

So irrespective of where your water is coming from now, there, there may not be any pollution, up river of you, but you know, as I said earlier, that rainwater, 80% comes from the oceans. You have microplastics floating on that surface layer of the oceans. They become part of the aerosol, along with all the chemicals that the plastic has absorbed.

That aerosol then forms the clouds. The clouds then form rain, comes back onto the land. So all the toxic chemicals that we are discharging all, all the lipophilic, hydrophobic, floating toxic chemicals and plastic that we discharge into the environment, comes back again as rain.

And that's why all rainwater except for rainwater, from trees, but 80% of all rainwater on the planet and 100% of rainwater derived from the oceans now contains microplastics at least 10 particles per liter, herbicides, pesticides, PFOS 100% contains PFOS, and at least five toxic forever chemicals.

So there is now no rainwater drinking water free from these toxic chemicals, and that's simply not sustainable because toxic forever chemicals build up in your body through a process of bioaccumulation.

You don't discharge them, they build up in your fat and various tissues and eventually that will cause cancer, or other conditions.

We have to stop this. We can't go on in this way.

[Xan Phillips]On that note, Dr. Howard Dryden from the Goes Foundation, thank you very much for speaking to us on Voice FM. We wish you your best endeavours for your research, but also in getting the word out amongst your fellow scientists, political thinkers, and leaders.

[Dr Howard Dryden] Your very welcome and thank you for the opportunity of talking about it.